Original author: RnDAO

Original title: What is a DAO Community and when is it healthy: a working paper by RnDAO

What is a DAO community and how to measure health has become increasingly important. The DAOrayaki community tracked this topic, and we found that RnDAO published a study on Measuring the Health of the DAO Community. In the research of RnDAO, we first put forward our views on the conceptual basis of defining the DAO community and how to measure the health of the DAO community. As we have seen in this article, the topic of DAO community health is very broad. From a systematic point of view, it is analogous to medical concepts and proposes indicators to measure the health of the DAO community. In the next phase of research, we will collect data from different communities to test and refine the community health model. Additional research projects (by us or others) could expand on the health assessment of different nested systems as well as the additional structures we propose. Likewise, exploring the contributors to the long-term health of communities could serve as further research.

Specifically, in this paper we attempt to answer the following questions:

#1 What are the characteristics of a community?

This topic is very broad and requires an explanation of how we understand what a community is, and what are its core characteristics. We conclude that it is an individual system at the microscopic level. However, it has several subsystems, and the community itself belongs to a larger ecosystem. This nested systems or network science view of communities guides our work, in addition to the view of social identity. We also noticed a dark side to the community (e.g. negative perception of outsiders, groupthink, etc.)

What are the characteristics of the #2DAO community?

After agreeing on what a community is, we explore definitions of DAO communities so we can compare them to other forms of community. We address this using several guiding questions, such as who is influenced and controlled, and how cohesive the community is.

#3 What is the health of the DAO community?

After pointing out that DAO communities have specific attributes that differentiate them from traditional communities, we delved into the question of what does it mean for a DAO community to be healthy? How do you distinguish healthy from unhealthy communities?

In line with our community systems view, we understand community health to be regenerative, and define it as the state of existence, interaction, and integration of individual and nested subsystems of a DAO community as they strive to achieve individual and collective goals.

#4 How do we assess the health of the DAO community?

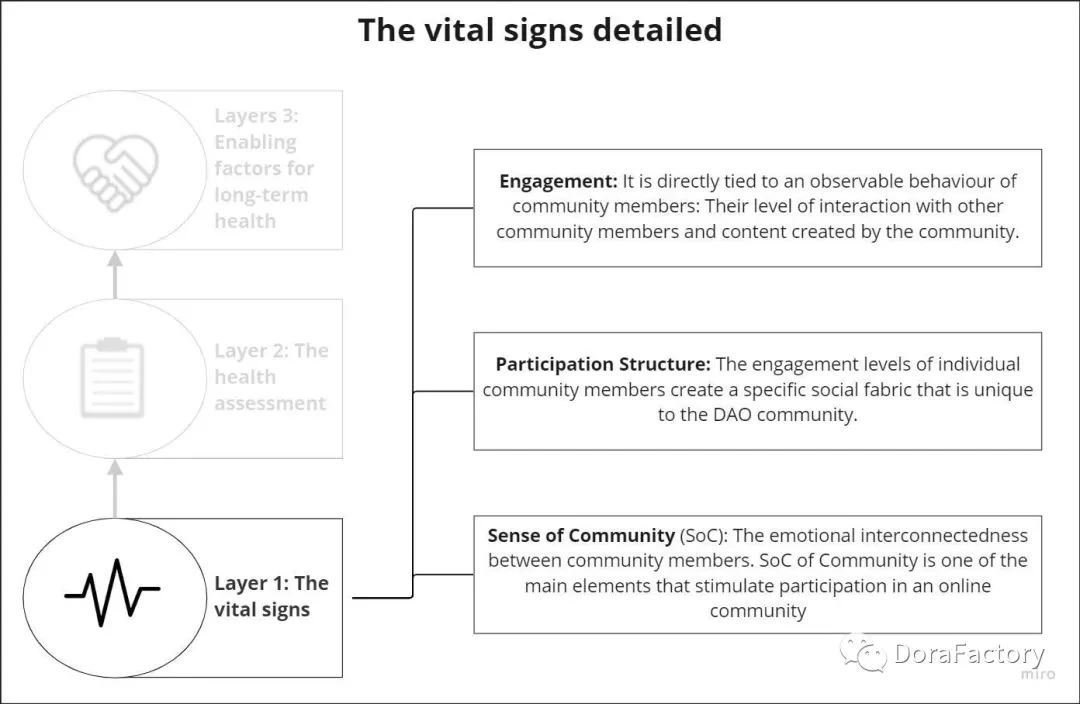

In this section, we explore how community health is studied, from definition to measurement. By analogy to medicine, we propose that several key signals can be measured to diagnose the health of a community and suggest engagement, participation structure, and community awareness. We recognize that these key signals primarily measure symptoms of community health. To better understand why, we identify specific avenues for further research and the need to work closely with the community to gain specific background knowledge.

#5 How do we think about measuring DAO community health?

In the final section, we give a high-level overview of what data we collect to measure key community signals.

Q1: What are the characteristics of the community?

1.1 Define the community

Community has been explored from multiple disciplines and perspectives, from biology to marketing, social psychology, network science, and more.

Here are some examples of how to describe a community:

Communities have shared values, norms, rules, and regulations (Chung, Kim, Shin, 2020).

A group of people who are connected by relationships and share a common identity and values (Ospina, 2017[1])).

Consists of: Membership, Influence, Reinforcement, and Shared Emotional Connections. (Martiskainen, 2016).

A self-organizing group of people who commit to supporting each other; they participate not only for their own needs, but also for the needs of others (Wheatley Frieze, 2006[2]).

Communities are Gemeinschaft[3] (Ferdinand Tönner 1957 [1887]) where personal and informal connections are common and interactions are shaped by social values.

A group of people is informally connected by shared expertise and passion for a shared enterprise (EC Wenger Snyder, 2000) [4].

Tight clusters in relational networks (Hu et al., 2008[5])).

Common to these definitions is that a community is made up of people who develop social relationships with each other. Because of these two characteristics, people within a community develop a shared identity, reinforced in shared values and a (deep) emotional investment in each other and the community.

Some sociologists (eg, Willmot, 1985; Lee Newby, 1983) agree to divide communities into three levels, including:

A place: where community members meet and interact with each other. Not limited to physical space.

A social structure (both arise from and shape the interactions of members).

A meaning or an identity.

Crow and Allan (1995) argue that these three levels interact and should not be viewed in isolation. In addition, the authors argue that a fourth dimension, time, should be considered when analyzing communities. By incorporating the time dimension, the evolution of communities can be explained. Communities contain forces that drive some out of the community and draw others in (Warwick Littlejohn, 1992). This opens the door to incorporating shared history into community checks. Communities are not only affected by recent events, but also by interactions that occurred weeks, months, or years ago. The temporal dimension is also necessary to examine how communities respond to external or internal disturbances, recover and adapt.

1.2 The ultimate meaning of the community

Humans participate in social collectives to increase their chances of meeting their needs through coordination. Following this axiom, we assert that a community will continue to exist as long as members perceive their participation in the community to be beneficial compared to other options that satisfy their needs.

Importantly, although a taxonomy of human needs is beyond the topic of this article, one need is of particular interest in the study of communities: it goes by different names—relationship needs, belonging needs, and kinship needs. As Baumeister and Leary found, existing evidence supports the hypothesis that the need to belong is a strong, fundamental, and extremely pervasive motivation (The Need to Belong, 2017) [6]. Community is not just a means to an end; community is an end in itself.

In the end, human self-awareness (and thus the need to define one) is a complex matter: we simultaneously desire to be unique and at the same time we want to belong to a group (Brewer Gardner, 1996) [7].

We identify with groups simply by our nature. However, the degree to which we identify with a social collective determines its impact on our lives. For example, in religious and racial conflicts, a strong identification with the social collective can lead individuals to perceive the collectives needs as their own, to the extent that they may sacrifice themselves (or others) to serve the collective.

There is a feedback effect between the individual and the community: no matter what the individual believes or does, in the end it comes down to forming an emerging community. This emerging community then begins to shape and direct the actions and thoughts of individual members.

They weave a web of reciprocity, giving and taking. [...] Through unity, survival. All prosperity is mutual. - Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweetgrass

1.3 The system perspective of the community

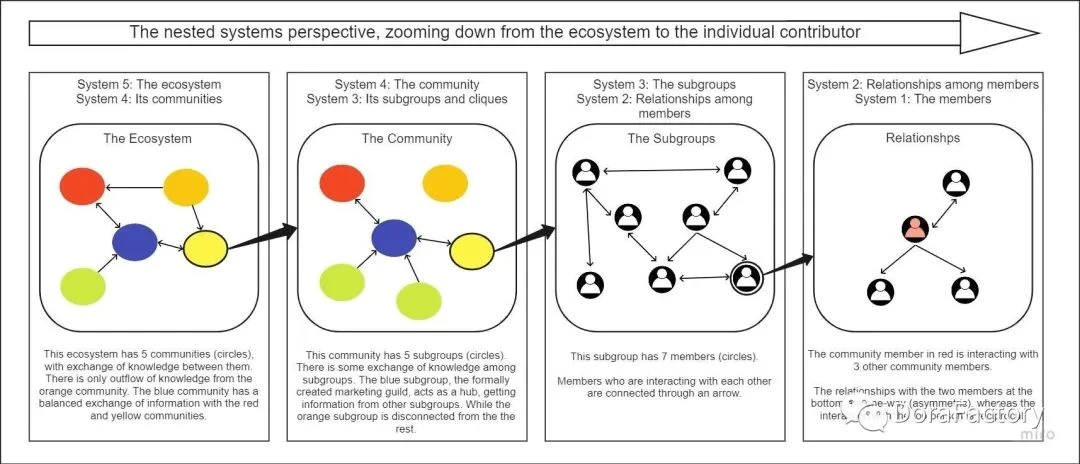

image description

Figure 1. Nested systems perspective

All system levels are interrelated, and interactions between different scales enable changes (or evolution or transformation or reorganization) at one scale to affect changes at other scales. The way systems connect and interconnect with systems at other levels is generally consistent across levels. At the community level, when considering what is optimally connected and what types of connections cause disease, we can learn from other systems that have been widely observed and studied (e.g. ecosystems, cells or the brain) inspiration. Drawing inspiration from interactive networks in biological systems when designing or improving human systems is an application of network biomimicry (van der Molen, 2022) [8]. Throughout the text, our views on communities and their health will be supported by examples of network biomimicry from various natural systems.

Coexistence with other communities and individuals

In addition to the vertical interactions between nested systems (interactions with the upper and lower layers), there are also horizontal interactions with other entities.

From an ecological point of view, an ecosystem is made up of various species interacting. These interactions can take different forms.

Antagonistic interactions: One species is harmed while the other species benefits. For example, predator-prey interactions between lions and lions. Lions prey on gazelles for breeding.

Reciprocal Interaction: Both species benefit from each other. Like the interaction between flowers and pollinators. Flowers provide food for pollinators, which in turn help flowers reproduce.

Competitive interaction: Two species negatively affect each other. For example, two different marine mammals compete for the same limited food source. ” van der Molen (2022)[9]

In our case, there may be antagonistic, reciprocal or competitive interactions at each level. For example:

Members attempting to allocate limited resources face the choice of antagonism (e.g. cheating other members), competition (e.g. competing for early completion of bounty tasks), and collaboration (e.g. creating proposals together).

Subgroups can capture (e.g. take over another groups jobs and rewards), compete (e.g. try to get a bigger budget for their guild), and collaborate (e.g. develop new abilities together).

Likewise, communities can capture (e.g. attack another community to destabilize it), compete (e.g. an arms race, offering better rewards for participation), or collaborate (e.g. jointly organize events and other mutually beneficial initiatives).

Some people join, some people leave

Finally, we assert that communities are open systems where members, ideas, and resources can enter or leave the community. The community is in the balance of these flows, and in particular (different types of) members can drive or limit other flows. The biological parallel is that proteins have higher turnover than cells, cells have higher turnover than organs, and organs have higher turnover than ecosystems (but individual species can also survive ecosystem collapse).

1.4 Community Dark Mode

Its important that the community doesnt always have to be positive. There are even gangs, cults and violent adherents. There are several dark patterns that communities can generate and adversely affect the ecosystem, including:

Negative Perceptions of Outsiders

Members who strongly identify with a community may have negative perceptions of outsiders, that is, people who do not belong to the same community. A good example is European football fans during derbies. Therefore, strong identification with the community can lead to intergroup stereotypes and trash talk (Hickman Ward, 2007) [10]. Strong identification with a group can lead to inflated positive attitudes towards those inside and unrealistically negative attitudes towards those outside. According to Molenberghs (2013, pg 1) [11], from a neurological perspective, we perceive the actions and faces of in-group members and out-group members differently, and we place more emphasis on in-group members. From Cell Biology A common symptom of cancer is that tumor cells move away from healthy cells by removing the gap junctions between them (Aasen et al., 2016) [12].

detrimental to the health of members

The desire to maintain groups can silence dissenting voices. For example, Barclay et al. (2004, pg 1)[13] found that “rural communities have informal social norms that tolerate certain types of crime and place restrictions on the reporting of such crime. Many victims of crime cannot . Fox-Rogers found that unequal distribution of community power can exacerbate destructive patterns such as umbrellas and corruption (“The Dark Side of Community”, 2019) [14]. Severely inhomogeneous power distributions are rarely observed in healthy biological systems. Instead, these systems self-organize in a decentralized manner (Camazine et al., 2020) [15].

inflexible

Through our identification with community, we transmit our instinct for self-preservation into cultural symbols, rituals, and ideas. These markers may be a functional response to a problem that is later ingrained in the identity fabric of the community. We tend to resist change as a way of maintaining our identity even when issues are no longer relevant and markers have lost their functional value. As Fisher Sonn (2002, pg 1)[16] pointed out, “The challenge of managing change is how to move forward, maintain those markers of true social value, incorporate new markers brought by newcomers, and develop together of the new label. In natural ecosystems, species that can adapt to changing environments will prevail. Meanwhile, species that are unable to adapt and continue their old behavior patterns are most likely to become extinct (Darwin, 2003) [17].

groupthink

When we rely on our communities to meet needs and desires and experience mutual benefit, we can view harmony as an (ostensible) indicator of the health of our communities as well as our own safety. Furthermore, the desire for consensus can inhibit dissent (or at least express disagreement). Thus, communities can experience groupthink, a phenomenon that systematically excludes (perceived) alternatives to group opinion (Solomon, 2006) [18]. Group members who share unique information are often disliked (Thomas-Hunt, 2003) because they express things that are unfamiliar to others. Stress and isolation (groups that are poorly connected to the outside world) significantly increase groupthink (Breitsohl et al., 2015) [19]. Unfortunately, “Different degrees of anonymity do not have a large impact on the likelihood of conforming to group opinions” (Tsikerdekis, 2013) [20].

unstable growth rate

A well-functioning community that meets the needs of its members attracts more and more new (potential) members. This is especially true for communities that are not solidified into a specific location. Due to the scalability of virtual platforms, virtual communities can develop within limited constraints. However, rapid growth can disrupt early intimacy, cohesion, and a general sense of community (Slemp et al., 2012) [21]. Since attention is a finite resource, the exponential growth of one community can drain and wipe out other communities, which in turn can destroy the ecosystem that sustains growing communities. The risk of unstable growth is also reflected in cancer. The rapid growth of tumor cells throws the whole body out of balance, eventually leading to the death of all cells in the body, including tumor cells (Houten Reilley, 1980) [22].

So far, we have defined what a community is and asserted that it will continue to exist as long as members perceive their participation in the community as beneficial (compared to other options for meeting their needs). We introduce the nested systems model, which describes communities as existing in hierarchies of nested systems. We also introduce network biomimicry, which draws inspiration from biological networks when building or improving human networks. We use antagonistic, reciprocal, and competitive interactions to describe the different ways in which system components interact, and we propose unhealthy aspects of communities and their relationship to unhealthy systems in biology. In the next sections, well define a DAO and describe the DAO community in depth, well define what DAO community health is, and well give an overview of how to research and improve DAO community health.

Q2: What are the characteristics of the DAO community?

2.1 What is DAO

Before describing the DAO community, we need to briefly describe what a DAO is.

In Conceptual Basis of DAO [23], (Ospina and Bohle Carbonell, 2022) [24] proposed the following definition of DAO:

A collective that exhibits organization, expression and evolution through various communicative events and processes, shaped by a shared spirit of emphasis:

Decentralized Power: There is no single source of authority.

Autonomy: Self-government, not subject to external coercion.

A common goal, vision or value that is (being) worked towards.

A shared treasury controlled by a decentralized voting mechanism.

From this definition, we can look for types of communities and compare them to DAOs and other collectives that exhibit organization in order to identify similarities and differences between these concepts and thus identify a conceptual basis for meaningful discussion of DAO communities and Avoid reinventing the wheel.

2.2 Understand the DAO community

Communities exist in many different shapes and forms. As we will see, we can distinguish DAO communities from other kinds of communities (eg, kinship communities), and we can also distinguish DAO communities from each other (eg, the structure of social DAOs versus protocol DAOs). To frame the discussion about DAO community attributes, we use the following five questions:

Who influences and controls the community?

Who is involved in the community?

Where does the community gather and interact?

What is the structure of the community? What is the bond and intent of the community?

What defines a communitys identity?

Who influences and controls the community?

A community can start as a group of people who settle in an area or meet regularly to engage in their favorite activities. Meanwhile, other communities are formally planned and sponsored by specific actors who want the community to exist. Lauden Traver (2003, as quoted by [25]Porter, 2004 [26]page nd[27]) distinguish between member-initiated and organization-sponsored communities: while member-initiated communities are created and managed by community members, organization-sponsored Sponsored communities start with sponsorship (commercial or non-commercial organizations such as governments, nonprofits, educational institutions). The community sponsored by the organization has key stakeholders and/or beneficiaries (e.g., customers, employees, students) who are important to the mission and goals of the sponsoring organization and thus will shape the community.

We cannot conclude that a DAO must start with member leadership or organization sponsorship, there are examples of both cases (i.e. a community gradually organizing into a DAO and a centralized organization building a community and gradually decentralizing into a DAO). Having said that, the motivations for creating a community can be different if it is formed from the bottom up or from the top down. Given real-world examples, we cannot claim that DAO communities are always member-led or organization-sponsored.

However, it is clear from our definition of a DAO that there are organizational aspects, as well as common goals, visions or values that are being worked towards and a shared treasury controlled by a decentralized voting mechanism. Thus, we can observe communities that co-exist and overlap with organizations, and watch their ambitions for (eventually) self-government.

Who is involved in the community?

Compared with traditional organizations, DAOs value decentralization and shared treasuries controlled by decentralized governance mechanisms [28] (Ospina Bohle Carbonell, 2022) [29]. So, ideally, DAOs are governed by their communities, and their communities become their stewards. As we will see, this in turn encourages specific patterns of participation and membership in the DAO community.

To date, community-led governance mechanisms have most often relied on the use of digital tokens, and while token systems vary in design, there are some common patterns: users often receive tokens (via airdrops and other mechanisms), labor provision Investors are also often compensated (partially or fully) in DAO tokens, with investors receiving tokens instead of shares. Tokens can be designated as utility (necessary to access a community or use a product, service or platform) or governance (enabling token holders to manage a DAO). Since they are transferable, they can be considered assets or used as investment vehicles.

The distribution of tokens among platform users, capital providers, and labor providers allows everyone to use tokens for platform services, participate in its value appreciation, and manage DAOs, which means that DAOs tend to consolidate stakeholders type. As a result, DAOs have closer-knit and hopefully aligned stakeholder types than traditional communities, increasing the chances of them merging into a single identity and community, namely DAO members.

Thus, traditional perspectives of research communities (such as communities of practice, branding, or even labor communities) may be too reductive to understand the various motivations of DAO community participants and the resulting interactions (e.g., knowledge sharing, peer support, co-create, co-shape, etc.).

Therefore, we can conclude that all stakeholders, whether they are investors, workers, or users, may often choose to participate in the community.

Where does the community gather and interact?

Early community literature emphasized the importance of shared geography (i.e. local communities). A community is linked to a particular community by its socioeconomic characteristics, and often kinship among community members. But with the advent of the internet and social media, virtual communities have multiplied, and so has the research on them.

A key differentiating factor between local and virtual communities is the way community members interact. Offline communities benefit from rich offline interactions (e.g., nonverbal communication, touch, smell), visual member identification (e.g., clothing, accessories, murals), and physical proximity. To add richness and texture to interactions, virtual communities must develop new ways to replace the dull text-based communication medium. Currently, this is done through emojis, memes, GIFs, videos, and increasingly 3D avatars). This distinction between virtual and local communities is important because mechanisms of interaction are critical for community members to build and strengthen relationships with each other.

To date, most DAO communities operate primarily online. Therefore, we will mainly refer to the virtual community literature to build our framework.

What is the bond and intent of the community?

Henri Pudelko (2003)[30] classify virtual communities according to two continuously changing dimensions:

Strength of social ties: The social cohesion between members of a community, i.e. a community can be a group of loosely coupled people or a tightly knit group. The authors argue that, depending on the intentionality of the communitys short- and long-term goals, members can be loosely and weakly connected, or form a tightly knit social group.

Degree of shared intention: Refers to the presence of shared goals and interdependence among participants (Bock, Ahuja, Suh, Yap, 2015; Gangi Wasko, 2009; Meirinhos Osório, 2009). The more conscious people are about why they form and participate in a community, the stronger the community will be.

DAOs differ along both dimensions, e.g. social DAOs are mostly about relationships between members, while protocol DAOs are mostly about the common goal of developing or maintaining the protocol.

DAO communities can mix stakeholder types and may have fairly fluid boundaries, however, they also tend to be self-governing (see The Ethos of DAOs, (Ospina Bohle Carbonell, 2022) [31], where DAOs maintain their own platforms and control the organization membership and access rights. DAOs thus typically consist of a highly aligned and tight-knit core team (who maintain and develop the platform and shape the organizational aspects), followed by casual contributors and peripheral people who are more like gamers or learning communities (members have weaker social ties, low intention to share, and interact primarily for personal entertainment or learning).

We conclude that DAO communities vary in their sharing intentions and strength of social ties between DAOs and between subgroups within each DAO.

What defines a communitys identity?

While the identity of each DAO and each DAO community will have unique elements, in general we can refer to four qualities shaped by the ethos of a DAO (section 2.1) as common factors that characterize a DAO community and possibly Thus distinguishing them from other communities (Ospina Bohle Carbonell, 2022) [32].

After the above theoretical review, we can draw five characteristics of the DAO community:

Symbiotic with Organizational Aspects (DAO).

Include multiple stakeholder categories with a tendency to merge them into one.

Mainly in the form of online gatherings (virtual communities).

The shared intentions and strengths of the social bonds within each DAO community vary across DAOs

In the spirit of DAOs (decentralized power; autonomy; shared goals, vision or values; and a shared treasury managed by the community).

Q3: What is DAO community health?

To borrow an analogy from the medical field, we think of a community as somewhat like a living organism. Although the traditional definition of health is based on the absence of disease, more recent definitions expand to see health as an emerging attribute and multidimensional structure:

“The complex systems on which our lives depend—ecosystems, communities, economic systems, our bodies—have emerging properties, foremost among which are health and well-being” (Goodwin et al., 2001, p.27 )

3.1 A regenerative perspective on community health

The 20th century view of health tended to view the body as a single organism. However, this organism is made up of the interplay of organs, which in turn are made up of interacting cells. Recent studies (eg Pflughoeft Versalovic, 2012 ) [33] have shown that, in addition to these cells, the human body includes microorganisms that coexist with human cells, contribute to human life and cannot be viewed in isolation. Likewise, some traditional views of community health describe the community as a single unit or simply a collection of individuals. However, as we have argued, a community consists of multiple nested systems that interact and depend on each other, among them:

individual member

Relationships between individuals (reciprocity or not) form community-specific structures of participation

Subgroups (formally created) and factions (informally created)

community as a whole

An entire ecosystem embedded in the community

Since these nested systems are interdependent, we argue that a community is healthy only if its subsystems and superimposed systems are also healthy. Therefore, a community that supports and promotes the health of these nested systems is considered to be (regeneratively) healthier.

3.2 Health is resilience, adaptability and transformation

Importantly, health is not just the absence of disease. Communities exist in ecosystems. This ecosystem is in constant motion: members interact within and across communities, people join or leave, and environmental changes in the ecosystem are affecting members and the community. To be healthy, beyond a planktonic state, a community needs to deal with these internal and external forces that shape it. This is consistent with Carillos (2017) [34] suggestion that communities are only healthy if they are able to function effectively, cope adequately, and change appropriately in response to internal and external stimuli.

Although naming conventions vary in various areas, we can highlight some necessary properties for a community to remain healthy. Communities with these attributes remain healthy or return to a healthy state after a period of turmoil. Drawing on Walker et al. (2004)[35]s discussion of sustainable and changing social-ecological systems, there are three attributes that describe the developmental trajectories that communities can experience. These properties describe increasing levels of agency in the system.

Resilience: The ability of a system to absorb disruption and reorganize to maintain the same function, structure, identity and feedback when undergoing change*.

Adaptability: the ability of actors in the system to affect resilience

Transformation: The ability to create entirely new systems when ecological, economic or social structures make existing systems unsustainable.

*Note: There is some intersection between the definitions of resilience and adaptability and transformation. We have chosen to retain this distinction in order to discuss community health assessment in more detail below.

community resilience

Community resilience refers to the ability of a community to return to its original state after internal or external events have impacted it (Matarrita-Cascante et al., 2017) [36]. Communities respond to events, dealing with tensions while seeking to restore their former stability. Here, the trajectory is purely reactive: events are processed by the system in order to regain the current state.

In network science, resilience is described as the time it takes for a system to return to equilibrium after a disturbance or change (Okuyama Holland, 2008; Thébault Fontaine, 2010) [37]. Resilience can come in two forms:

Migration resilience (species extinction): From a DAO perspective, disturbances can be contributors who leave involuntarily or voluntarily (eg, stop participating in the community). Other DAO members may rely heavily on this persons presence, and without them, other members may in turn leave. The persistence of the community reflects the number of community members that remain after reaching a new equilibrium in response to the departure of community members. The ecological version here is that one species goes extinct, leading to mass extinction.

Added Resilience (Invasions): From a DAO perspective, a disturbance could be a contributor joining the community. While most communities will be able to absorb disturbances from a single contributor joining, the effects of joining a large number of contributors can have negative effects in the community. Imagine if a large number of inexperienced or value-aligned members joined a DAO, weakening the identity of the community. Likewise, the health of the community can suffer if malicious actors come in and try to seize its governance.

Network perspectives on resilience can be enhanced by referring to insights from other research areas. For example, psychological perspectives focus on individual resilience and define resilience as “the existence, development, and participation of community resources in which community members thrive in environments characterized by change, uncertainty, unpredictability, and surprise” (Berkes Ross, 2013) [38]. We consider the individual as the lowest level of our systems view of community health. Naturally, their resilience affects the resilience of other systems, just as the resilience of cells affects the resilience of organisms, and how the resilience of organisms affects the resilience of ecosystems. Another perspective is a socio-ecological perspective on resilience. This perspective sees resilience as a conscious action aimed at enhancing the individual and collective capacity of community members and institutions to respond to and influence the course of social and economic change (Berkes Ross, 2013) [39].

Adaptation: Learning and Antifragility

In addition to a systems ability to resist or recover from shocks (i.e., resilience), there is also the ability of a system to adapt so that it can avoid future shocks and increase its resilience. In this development trajectory, the community takes a more active stance, aiming to do something in response to external shocks, rather than just returning to the status quo.

In order to adapt, DAO communities need to learn continuously; in other words, they need to adopt elements of a learning organization (Senge, 2006) [40]. Organizational learning is “the process by which organizations continuously question existing products, processes, and systems, determine strategic positioning, and apply various learning models” (Wang Ahmed, 2003, pg. 14) [41].

Organizational learning, as defined by Wang and Ahmed, provides us with (somewhat) a holistic view of adaptability. A community can only adapt if its members (continuously) learn and its culture evolves. Additionally, it needs to have processes in place to change its processes, capture and distribute its knowledge, and continuously improve as a collective.

More recently, as the concept of organizational learning has been increasingly expanded to include aspects of creativity and (disruptive) innovation, it has been linked to another concept applicable to communities: antifragility—the behavior of systems in response to stressors. The ability to react to lead (Taleb 2013 [42]). In other words, antifragile systems have learned (adapted) in such a way that they benefit more from negative shocks and disturbances than from positive events. Taleb (2003) viewed negative shocks as random events that could be errors in the system or one of its subsystems. From the perspective of our nested systems, we want to include shocks from the supersystem (environment) as potential sources of negative shocks. A community that is not antifragile will deal with the tension that comes with shocks and return to its false default state. As such, it fails to learn from the disturbance and will suffer setbacks from subsequent negative events.

Achieving adaptation (and further antifragility) requires individual and collective levels and enablers between them:

At the individual level, this involves personal capabilities such as cognitive flexibility (Dane, 2010) [43], and resources such as social capital, which (Nahapiet Ghoshal, 1998) [44] has been shown to enable individuals to learn and adapting to new work and professional environments (Armanda Hamtiaux Claude Houssemand, 2012; Oh et al., 2022) [45].

At the intersection of systems, adaptation is enabled by the ability of individuals (or subsystems) to make and execute choices, leading to collective adaptation, i.e. bottom-up governance or grassroots movements.

At the collective level, adaptation needs

collective intelligence (i.e., collective consciousness making, meaning making, and choice making) and collective leadership (Por, 2008) [46],

Collective capacity, ie community capacity, the ability to get work done to implement change (Laverack, 2005) [47].

transformation

Finally, beyond the systems ability to adapt, the system needs transformation. This happens when a system reaches an evolutionary dead end—a point from which it can no longer adapt to continue serving its purpose. A community on a transformational trajectory fundamentally changes itself and becomes a whole new system.

In biology, an evolutionary dead end leads to death and decomposition. However, the constituent elements are the basis for generating new life. In science, we can compare changes in scientific paradigms to changes in an old worldview, in which exceptions and inconsistencies accumulate in the old worldview until it falls apart and is replaced by a new worldview. This new worldview may retain elements of the old.

Traditionally, weve been more concerned with resilience or adaptability than transformation. A Google Scholar search for “community resilience” yields 3,000,000 results, “organizational resilience” 188,000, “community adaptation” 624,000, and “organizational adaptation” 112,000, while “community transformation” yields only 18,500 results and “organizational transformation” 17,200 . Importantly, the term transformation is frequently used in the papers found, with a definition closer to adaptation than to actual transformation. In DAO, however, there are already some elements that directly enable transformations:

On an individual level, community members can quit in anger, leaving the community and taking their share of the collective asset with them.

At the subgroup or faction level, a subset of community members can fork, copying the DAOs smart contracts into new organizations.

Some traditional barriers to transition (such as non-compete agreements and non-disclosure agreements) are largely absent in DAOs.

3.3 DAO Community Health

Having covered communities (nested, interdependent systems) and regenerative perspectives on resilience, adaptation, and transformation, we now aim to bring these concepts together to form DAO community health, and qualified health (multidimensional spectral health) Uniform definition. Therefore, we define DAO community health as:

(“The state of existence, interaction, and integration of individual and nested subsystems of the DAO community as they strive to achieve individual and collective goals”)

Healthy or not:

According to the above definition, a DAO community is considered healthy (actively healthy) if the status of the community is as follows:

Contributing (or at least not breaking) its nesting system and itself:

Meeting the needs and wishes of members (including aligning with their values, e.g. the ethos of the DAO);

Promote healthy relationships, and functioning subgroups and factions;

Advance its collective goals (community capacity to create value for the DAO as a whole);

Contribute to a healthier ecosystem.

image description

Figure 2: A healthy DAO community

Conversely, an unhealthy neighborhood is one that fails to satisfy #1 or #2 above. As a result, patterns may manifest, which we covered in the section on dark patterns in communities: negative perceptions of outsiders (overcompetition), rigidity (lack of adaptability), groupthink (collective stupidity), damage to members health and Unstable growth rate (non-regenerating).

Finally, we can define a series of stages in between (between the theoretical extremes of fully positive health and fully negative health) based on the ability of the community to realize the different components.

Q4: How do we assess the health of the DAO community?

4.1 Assessing the health of the DAO community

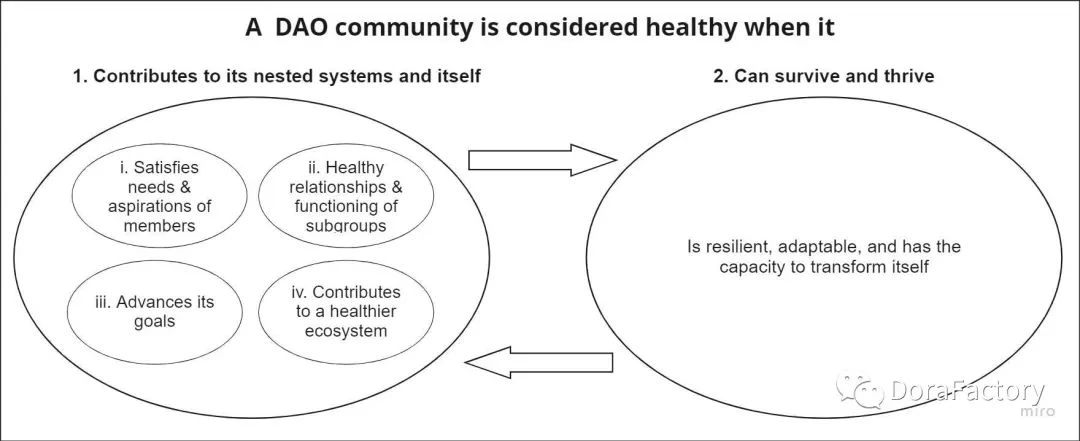

image description

Figure 3: How we assess community health

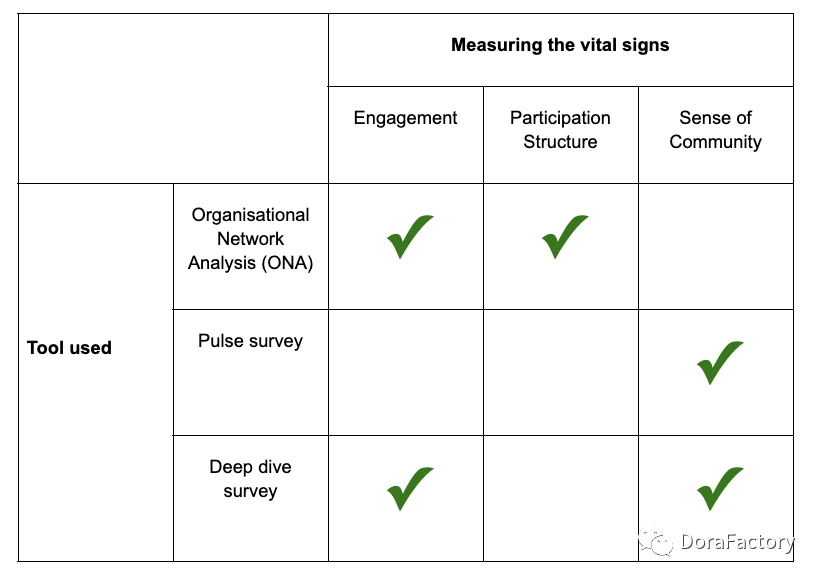

4.2 Key signals: participation, structure and sense of community

We assert that the health of a community can be rapidly assessed (at a particular point in time) through three lenses:

Participation.

Structure of member interactions (structure of subsystems).

Members sense of community.

These snapshots can be taken at different time periods (e.g. daily/weekly/monthly; pre-season, season, post-season). By combining frequent passive data collection, such as daily messages on a chat platform, with less frequent active data collection, such as quarterly surveys and weekly pulse surveys, we balance depth of insight with member disruption. These snapshots add to the dynamic view of community health, providing opportunities to link specific actions and events to changes in community health. Thus, enabling community managers to assess their impact and communicate it to other stakeholders.

Our definition of community health includes five dimensions:

community member

relationship between two members

Community

Community

Greater Community Ecosystem

When we take a regenerative systems view of community health, the health status (positive or negative) of one system will affect neighboring systems.

The key signal we chose, participation measures the activities of community members rather than their overall health (physical, psychological, etc., including not only the treatment of disease but also its social origins McKee, 1988; Saylor, 2004) [48] . We hypothesize that a persons overall health affects their activity. Thus, a direct measure of an individuals overall health will be made while exploring the favorable factors for long-term community health. Likewise, measuring the health of the larger ecosystem is a critical but difficult task, as we need to measure the structure of participation across DAO communities. However, keeping the ecosystem in mind, we will track general events that have an impact on the DAO community (e.g. rise/fall of cryptocurrencies, sentiment analysis of web3 news).

image description

Figure 4: Detailed key signals

4.2.1 Engagement

Engagement is directly related to the observable behavior of community members: how well they interact with other community members and what content the community creates. Lack of engagement can be seen in: no conversations, content not being shared, and events not being attended. Participation is thus synonymous with the involvement of community members in the community.

According to Etienne Wenger (1999) [49], there are different trajectories of participation in the community:

Peripheral trajectories correspond to full participation

Inbound trajectories describe newcomers expressing a willingness to fully participate in the community and to continue participating in the future.

Internal trajectories are those members who have achieved full participation. Their engagement trajectories center on the evolution of the community and their regenerative place within it.

Boundary trajectories As participants struggle to maintain identities across community boundaries,

Outbound trajectories are activities that leave the community.

Another distinction in participation is between public and private interactions. Public interactions are visible to all, while private interactions are private chats with a few behind closed doors. Interactions that occur in private messages or in small closed communities give community members the opportunity to develop intimate and deep relationships with others (tight social capital) (Donath, 2007) [50], while interactions in open spaces allow community members to communicate with many Others interact and build a broad network of acquaintances (bridging social capital) (Lee et al., 2014) [51]. Further research shows that communicating with others in an open space stimulates people to form deep and shallow relationships, while private communication only helps to strengthen relationships (Li Chen, 2022) [52]. Both forms of social capital, ties (deep relationships) and bridges (acquaintances), help community members develop a sense of community (Li Chen, 2022) [53].

Importantly, participation should not be limited to the interactions described above. As we have seen, the DAO community thrives through an ecosystem of interactions among diverse stakeholders that come together, making health an emerging attribute. Therefore, over time, we will strive to expand the scope and types of interactions that can be collected in the data to enrich our measurements of the health of the DAO community.

4.2.1.1 Latency

Latent not discussed above is as a form of passive participation (Nonnecke Preece, 2001) [54]. Its a form of engagement that stems from virtual communities. Latent community members are visiting virtual spaces of the community (e.g., forums, Discord, Reddit, Twitter, or other social media channels), but are not visibly interacting with any content in any way: they do not respond with emoji or text, nor Do not participate in activities.

Considering lurkers is important because as many as 90% of people who join a community do not become active in the first place (Nonnecke Preece 2000; Schneider et al., 2013, as quoted by Trier 2014 [55]). We speculate that lurkers reading posts and thus consuming the content of the community may share it in other communities and integrate it into their daily practice (Takahashi et al., 2003) [56].

In the case of DAOs, Lurkers may make significant contributions by serving as ambassadors and evangelists across the community, helping to direct attention and resources. However, it is also possible that a large number of lurkers poach information and insights and transplant them to other (possibly competing) communities without giving back. This form of cross-DAO information sharing may benefit the entire DAO ecosystem, assuming a balanced flow of information in and out; and also benefit individual DAOs (Thébault Fontaine, 2010; C.-C. Wang et al., 2017 )[ 57].

In general, the free flow of information may facilitate the development of the entire ecosystem, but raises questions about sustainability at the community level, which each community needs to consider on its own unique circumstances. Additionally, since lurkers remain anonymous, their presence affects trust and a sense of community.

Lurkers do not post and therefore do not establish an identity in the online community. Their anonymity, therefore, leads other community members to wonder with whom they share this online space. In the end, Lurkers themselves suffer for keeping silent. Lack of participation in public dialogue reduces their sense of community, as they do not develop any tight social capital and deep relationships with others (Li Chen, 2022) [58].

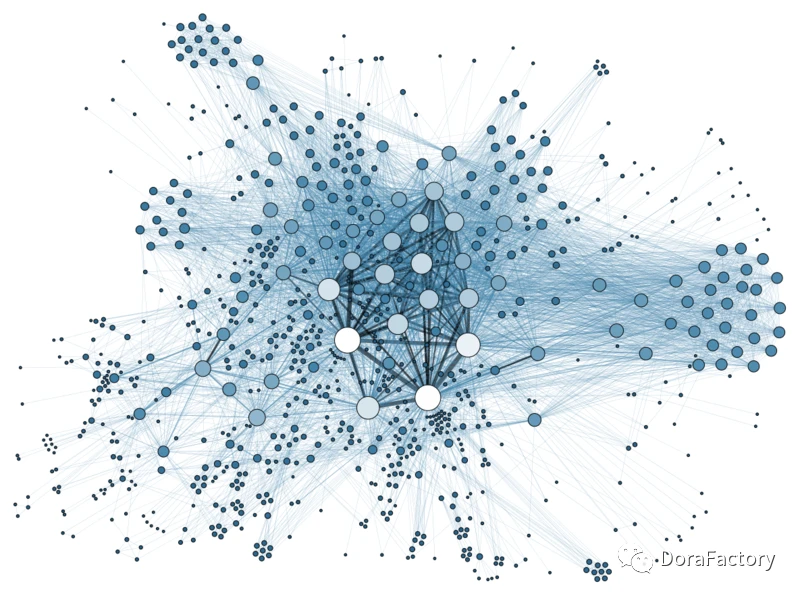

4.2.2 Participation structure

image description

Figure 5: Social Network Visualization (Grandjean, 2016)

Social networks, patterns of interaction between humans, have been studied for many years. Researchers have investigated the effect of network structure on peoples choices (e.g., adopting an innovation, eating a Big Mac) and outcomes (success and failure) (Borgatti Halgin, 2011) [59]. The common hypothesis of social network scientists is that connections between people help them exchange things like information, energy, and goods (network flow models) or coordinate actions and beliefs, such as peer pressure and protest (network bond models).

When we look at DAO community health (DAO communities are nested systems of interdependence) from a renewable perspective, it is worth considering network biomimicry. We can apply a variety of biological model systems, but special emphasis is placed on network studies from ecology because of the extensive research in this field spanning decades. As we mentioned, a DAO community has different stakeholders (investors, workers, users, etc.), what ecologists call species, and we can also conceptualize different operational skillsets (developer , marketers, designers, etc.) as a species. In contrast to social science network studies, ecology focuses on factors that cause population growth or decline within ecosystems, and thus can allow us to understand the dynamics within communities that may lead to their success or failure. Likewise, the types of stakeholders can be viewed as cell types or brain regions, and we will briefly mention examples relevant to these system types.

Early network research using computer models showed that as networks grow in size and complexity, network resilience tends to decrease (May, 1972) [60]. Observational studies in ecology have shown that ecosystem resilience increases with increasing complexity (Hedgpeth. 1954; MacArthur. 1955) [61]. In the ensuing decades, extensive research has shown that this increased resilience is a consequence of specific network structures present in ecosystem networks (Landi et al., 2018; van der Molen, 2022) [62]. Thus, ecosystems that grow in size and complexity can become more resilient if the interaction patterns among ecosystem members are supportive. For example:

Moderate number of clusters: In networking, a cluster is a group of community members who primarily interact with most or all members of the group. They form a bottom-up subsystem with no formal incentives. When such clusters exist in moderation, there is still limited interaction between members of different clusters. This is known as the small world effect (Watts Strogatz, 1998) [63]. A community is described as a small world if two conditions are met: it has factions, which provide space for members to discuss niche topics and facilitate local information processing, and it has crossovers, connecting these niches to ensure global information integration . Interestingly, protein interaction networks in cells and brain regions also interact like small worlds (Bassett et al., 2006; Goldberg Roth, 2003) [64].

Variation in the number of relationships among members: Some members of an ecosystem are connected to many other members, while other members interact with only a few. In ecology, a member who is related to many other members is described as a generalist. In the social sciences, they are called popular members or workhorses. Online communities often exhibit this uneven long-tail distribution, which is also observed in many other biological systems, including cells and brains (Almaas Barabási, 2006; Tomasi et al., 2017) [65].

Strong ties serve as the backbone, but most ties are weak: certain members have strong influence over each other, creating a stable framework for the community. However, most members rarely interact with each other, which allows the community to be flexible to change. This structure reflects the balance between social capital ties and bridging (Li Chen, 2022) [66]. A similar strong-interaction scaffold supporting a large number of weaker interactions has also been observed in the brain and self-organized cerebral organoids (Sharf et al., 2022; Song et al., 2005) [67].

Connectedness: When people have more relationships with other people in the community, it leads to a more stable community. Because of the redundancy in the way information is passed from one person to another, information can spread more easily in a community (Thébault Fontaine, 2010) [68]. More independent pathways connecting each pair of members in a community leads to higher social cohesion within that community (White Harary, 2001) [69] and is a sign of long-term community stability (Quintane et al., 2013) [70 ]. Likewise, redundancy in brain networks supports cellular and brain function (Bettinardi et al., 2017; Cutler McCourt, 2005) [71].

Reciprocal and Competitive Interactions: Some interactions are beneficial to both parties involved, while others are competitive. Both types of interactions contribute to community stability (Mougi Kondoh, 2012) [72]. For example, in a DAO, members contribute their unique skills in a collaborative effort towards the overall goal of the DAO (mutual benefit). At the same time, DAO members can compete with each other to come up with the best solution and implementation (competition). For example, it helps to promote high-quality proposals by submitting competing proposals in an attempt to earn a bounty. Likewise, in biological networks, many proteins have the sole or primary function of enhancing or silencing other proteins (Duan Walther, 2015) [73].

4.2.3 Community Awareness

In contrast to observable health measures of engagement, sense of community (SoC) cannot be observed but can only be inferred from other data points. SoC is an emerging state that describes the emotional connection between community members

Researchers believe that a sense of community is one of the main factors motivating online community participation (Blanchard, 2008; Luo et al., 2017; Talò et al., 2014 ) [74]. A sense of community creates motivation for people to log into online communities. Furthermore, it creates emotional bonds with other community members similar to what people feel from friends in real life (Abfalter, Zaglia, Mueller, 2012; Luo et al., 2017).

According to Blanchard (2008), important predictors of virtual community awareness are the presence of shared norms, people supporting each other, and building identities in online communities. Similar to this definition, we conceptualize community awareness as:

Membership: a sense of belonging and identification with a community, a shared symbol system.

Common Norms: Members (in part) share a common understanding of acceptable behavior. Behavior here refers to the style of communication in both text-based and video-mediated communication. Text-based communication includes words, pictures (eg, gifs), and emoji.

Community identity: Members develop a community-specific identity and, through this identity, perceive a responsibility to the community. This community-specific identity may differ from the identities that members have developed in different communities. In order not to destroy their connection to the community, members intentionally avoid forming identities that are too unique and mimic other community members to some degree.

4.3 Contributors and additional perspectives on nested systems

As we have seen, key signals already provide us with extremely rich information across different nested systems, even possessing some predictive power. However, we can go further. Here is a non-exhaustive list of constructs that may provide some additional insight:

Agency, Autonomy and Sovereignty

trust and psychological safety

Incentive and Motivation Perspectives

Technology Acceptance Model

psychometric analysis

overall health assessment

Measure across communities to derive ecosystem health

Q5: How do we think about measuring key signals?

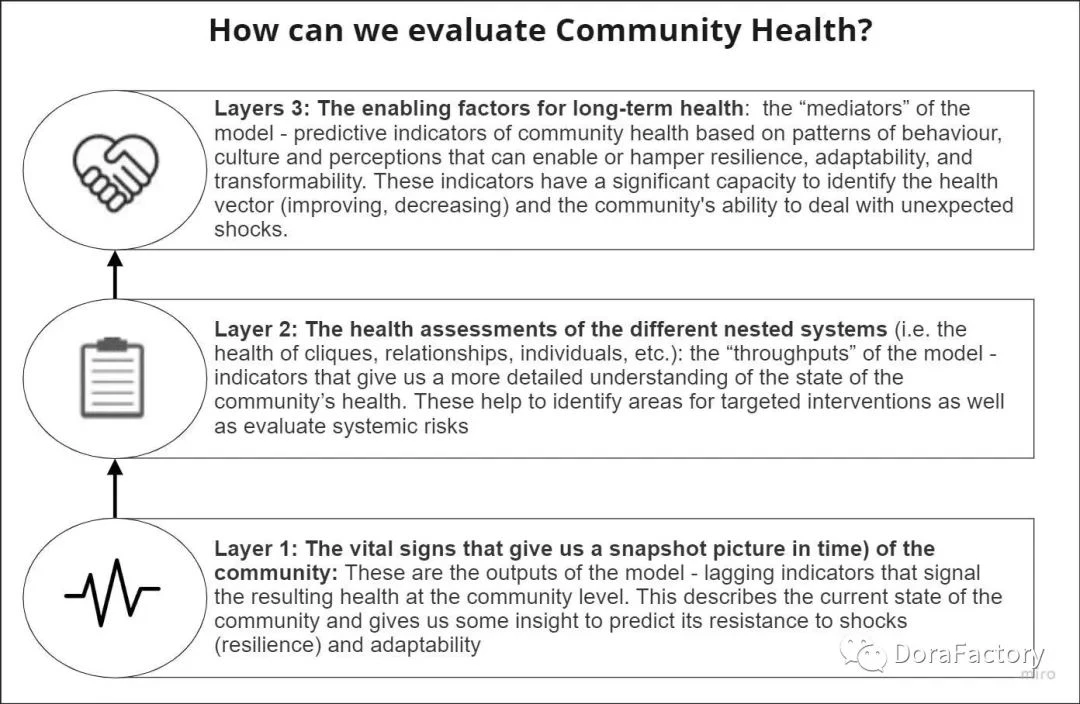

image description

Figure 5: Measuring key signals

The participation of community individuals is measured by their activity in the community. This refers to their posting behavior and event attendance. Specifically, we measure their position in the community and how it evolves over time to calculate the Proportion. Finally, we will also measure the proportion of community members in the community that span different subgroups and factions. These people hold key positions because they are able to exchange information between smaller groups.

When measuring engagement structures, our goal is to determine the ability of communities to grow sustainably in size and complexity. As a data source, we use interaction data of community members. Interaction data is members posts in the public channels of the communitys online forums. By using this data source, we are reducing the burden on community members as they do not have to fill out surveys and recall their engagement patterns. Furthermore, this data collection strategy is less prone to recency and significance biases. A leading indicator of participation structure is the small-world metric, which reflects the balance between clusters in a network and the crossovers that connect these clusters into a cohesive whole. In addition, we will investigate the distribution of the number of interactions among different members and the distribution of the intensity of these interactions to assess community resilience.

To measure community awareness, we are using scientifically validated surveys. By using surveys, we are able to gain insight into individuals perceptions and feelings about the community. The Brief Community Awareness Measure was proposed by David McMillian, one of the authors who first described the theoretical framework. Starting with the original 8-item survey, in our Pulse survey we decided to focus on only two questions that assess the emotional connection of individual members. We decided to do this because pulse surveys are usually very short (2 to 5 questions). The dimension of emotional connection was chosen because it had the strongest association with the overall construct of a sense of community.

A note on individual and ecosystem health as well as resilience, adaptation and transformation.

Although measuring these dimensions is beyond the scope of key signals (the starting point of our community health), we can gain information about them now that we have collected the data.

For example, a sense of community has been shown to be an indicator of community resilience and individual health.

Furthermore, to measure community resilience, we can calculate how participation structures change over time. Communities that regain their original (healthy) levels of participation, participatory structures and sense of community are considered resilient. The accuracy of resilience measurements depends on the time frame chosen and the internal and external events that occurred during the data collection period. Before measuring a communitys resilience, it is important to first determine what its baseline level is and whether that baseline level is considered healthy for a particular stage of community maturity.

Finally, we have seen that the structural elements that enable efficient information flow are directly related to the adaptive capacity of communities (Matarrita-Cascante et al., 2017) [75], while weak adaptation) may lead to de-identification and thus be reflected in a sense of community.

further research

references

references

https://medium.com/conductal/the-difference-between-communities-groups-and-networks-179ac2052f25

https://www.margaretwheatley.com/articles/emergence.html

https://www.thoughtco.com/gemeinschaft-3026337

https://hbr.org/2000/01/communities-of-practice-the-organizational-frontier

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18850911/

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?pExmzo

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?6Ci7Ck

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?2X9Mzk

https://mirror.xyz/0x228F308e90C36eF1aceE0BEC99061f9De65dbCdd

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?GrTIds

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?ExdeP3

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?F5W39M

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?nhq5j3

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?Ncr2ja

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?EZhrnq

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?WoSleU

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?jcOnMV

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?7YDP74

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?pe7gd8

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?g5absm

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?yEE2Rx

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?irWmDS

https://mirror.xyz/0x8B580433568E521ad351b92b98150c0C65ce69B7/1zGqbsh1YZNi3I9yvtk_2VMcpyg_dvHF1GlZ_LAO3p4

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?G3a9sB

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?broken=VfEk0U

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?xUOwVW

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?f7zPPt

https://mirror.xyz/0x8B580433568E521ad351b92b98150c0C65ce69B7/1zGqbsh1YZNi3I9yvtk_2VMcpyg_dvHF1GlZ_LAO3p4

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?75niyK

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?iolZGU

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?Gnid5t

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?dyhhsr

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?UDc3Ej

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?0n6AVI

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?sgHsjh

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?dKOyce

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?VBc3Q2

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?R4jiJc

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?SRK0JS

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?Kvdmlu

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?BBO7Z6

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?FGUTHI

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?vlGBYK

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?gCy4pM

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?5EFaTQ

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?tsPgJ6

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?3C0R0y

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?85Fu6H

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?CmYgaf

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?8NOvi1

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?QnC6QM

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?qvNGYL

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?BVWG5s

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?hvUme8

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?vzFMuf

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?pyBJF9

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?80Iaf6

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?jKX1o9

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?O3NkXB

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?3cpU6r

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?O3q3m8

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?TV3Neq

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?Oc3pcW

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?MdRAs8

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?nxAIRd

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?iBsA7T

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?fqcKa0

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?NLwqpT

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?ozwBPe

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?y7ccK1

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?c8ISQ7

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?HYasNu

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?SRgt4j

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?VOsZJB

https://www.zotero.org/google-docs/?ausNlx