Original article by Rick Maeda

Compiled by Odaily Planet Daily Golem ( @web3_golem )

The fact is that most encryption users are not hacked through complex vulnerabilities, but are attacked by clicking, signing, or trusting the wrong things. This report will analyze in detail these security attacks that happen to users every day.

From phishing kits and wallet stealing tools to malware and fake customer service scams, most attacks in the crypto industry are directed at users rather than protocols, which makes common attacks focus on human factors rather than code. Therefore, this report outlines cryptocurrency vulnerabilities for individual users, covering not only a range of common vulnerabilities, but also real-world case analysis and things that users need to be vigilant about in their daily lives.

You are the target of attack

Cryptocurrency is designed to be self-custodial. But this fundamental property and core industry value often makes you (the user) a single point of failure. In many cases where individuals have lost their cryptocurrency funds, the problem was not a protocol vulnerability, but a click, a private message, a signature. A seemingly insignificant daily task, a moment of trust or negligence, can change a persons cryptocurrency experience.

Therefore, this report does not target smart contract logic issues, but rather individual threat models, analyzing how users are exploited in practice and how to respond. The report will focus on vulnerability attacks at the individual level: phishing, wallet authorization, social engineering, malware. The report will also briefly introduce protocol-level risks at the end to outline the various vulnerability exploits that may occur in the cryptocurrency field.

Analysis of vulnerability attack methods faced by individuals

The permanence and irreversibility of transactions that occur in a permissionless environment, typically without the involvement of intermediaries, combined with the need for individual users to interact with anonymous counterparties on the devices and browsers that hold financial assets, makes cryptocurrencies a coveted hunting ground for hackers and other criminals.

Below are the various types of vulnerabilities that an individual may face, but readers should note that while this section covers most types of vulnerabilities, it is not exhaustive. For those who are not familiar with cryptocurrency, this list of vulnerabilities may be dizzying, but a large part of them are regular vulnerabilities that have already occurred in the Internet age and are not unique to the cryptocurrency industry.

Social Engineering Attacks

Attacks that rely on psychological manipulation to deceive users into compromising their personal safety.

Phishing: Fake emails, messages, or websites that mimic real platforms to steal credentials or recovery phrases.

Impersonation scams: Attackers impersonate KOLs, project leaders, or customer service personnel to gain trust and steal funds or sensitive information.

Mnemonic scams: Users are tricked into giving away their recovery phrases through fake recovery tools or giveaways.

Fake airdrops: luring users with free tokens, triggering unsafe wallet interactions or private key sharing.

Fake job offers: Disguised as employment opportunities but designed to install malware or steal sensitive data.

Pump and dump scams: Selling tokens to unsuspecting retail investors through social media hype.

Telecommunications and Account Takeover

Exploiting telecommunications infrastructure or account-level vulnerabilities to bypass authentication.

SIM swapping: Attackers hijack a victims mobile number to intercept two-factor authentication (2FA) codes and reset account credentials.

Credential stuffing: Reusing compromised credentials to access wallets or exchange accounts.

Bypassing two-factor authentication: Exploiting weak or SMS-based authentication to gain unauthorized access.

Session hijacking: Stealing a browser session through malware or an unsecured network to take over a logged-in account.

Hackers used SIM card swapping to gain access to the SEC Twitter account and post fake tweets

Malware and device vulnerabilities

Hacking into user devices to gain access to wallets or tamper with transactions.

Keyloggers: Record keystrokes to steal passwords, PINs, and recovery phrases.

Clipboard hijacker: replaces the pasted wallet address with an address controlled by the attacker.

Remote Access Trojans (RATs): These allow attackers to take full control of the victim’s device, including their wallet.

Malicious browser extensions: Compromised or fake extensions can steal data or manipulate transactions.

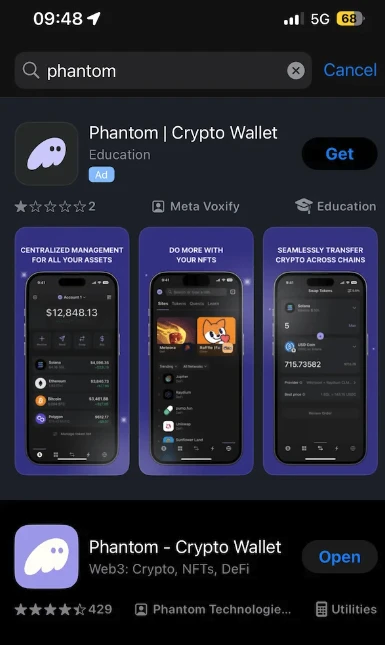

Fake wallets or applications: Fake applications (apps or browsers) that steal funds when used.

Man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks: Intercept and modify communications between a user and a service provider, especially over an unsecured network.

Unsecured WiFi Attacks: Public or compromised WiFi can intercept sensitive data while logging in or transmitting.

Fake wallets are a common scam targeting cryptocurrency newbies

Wallet-level vulnerabilities

Attacks on how users manage or interact with their wallets and sign.

Malicious authorization draining of funds: A malicious smart contract exploits a previous token authorization to drain tokens.

Blind signature attack: A user signs an obfuscated transaction condition, resulting in loss of funds (e.g., from a hardware wallet).

Mnemonic theft: Leaking of mnemonics through malware, phishing, or due to poor storage habits.

Private key compromise: Insecure storage (e.g., in a cloud drive or plain text note) leading to key leakage.

Hardware wallet compromise: Tampered or counterfeit devices reveal private keys to attackers.

Smart Contract and Protocol-Level Risks

Risks arising from interacting with malicious or vulnerable on-chain code.

Rogue smart contracts: Hidden malicious code logic is triggered when interacting, resulting in funds being stolen.

Flash loan attacks: using uncollateralized loans to manipulate prices or protocol logic.

Oracle manipulation: Attackers tamper with price information and exploit protocols that rely on erroneous data.

Exit liquidity scams: Creators design tokens/pools where only they can withdraw funds, leaving users stranded.

Sybil attack: Using multiple fake identities to disrupt a decentralized system, especially governance or airdrop credentials.

Projects and market manipulation scams

Scams related to tokens, DeFi projects, or NFTs.

Rug scam: The project founder disappears after raising funds, leaving behind worthless tokens.

Fake projects: Fake NFT collections trick users into committing scams or signing harmful transactions.

Dust attacks: Utilize tiny coin transfers to de-anonymize wallets and identify phishing or scam targets.

Network and infrastructure attacks

Leverage the front-end or DNS-level infrastructure that your users rely on.

Frontend hijacking/DNS spoofing: Attackers redirect users to malicious interfaces to steal credentials or trigger insecure transactions.

Cross-chain bridge vulnerability: stealing user funds during cross-chain bridge transmission.

Physical threats

Real-world risks, including coercion, theft, or surveillance.

Physical attacks: Victims are coerced into transferring funds or revealing their seed phrase.

Physical theft: Stealing a device or backup (e.g., hardware wallet, laptop) to gain access.

Shoulder surfing: Observing or filming a user entering sensitive data in a public or private setting.

Key vulnerabilities to watch out for

While there are many ways that users can be hacked, some vulnerabilities are more common than others. Here are the three most common attacks that individuals who hold or use cryptocurrency should be aware of, and how to prevent them.

Phishing (including fake wallets and airdrops)

Phishing predates cryptocurrency by decades, with the term coined in the 1990s to describe attackers “fishing” for sensitive information (usually login credentials) through fake emails and websites. As cryptocurrency emerged as a parallel financial system, phishing naturally evolved to target seed phrases, private keys, and wallet authorizations.

Cryptocurrency phishing is particularly dangerous because there is no recourse: no chargebacks, no fraud protection, and no customer service to reverse transactions. Once your keys are stolen, your funds are gone. It’s also important to remember that phishing is sometimes just the first step in a larger attack, and the real risk is not the initial loss but the cascading damage that follows, such as compromised credentials that allow attackers to impersonate victims and defraud others.

How does phishing work?

The core of phishing is to exploit human trust by presenting a false trustworthy interface or impersonating an authority figure to trick users into voluntarily handing over sensitive information or approving malicious operations. The main transmission channels are as follows:

Phishing Websites

Fake versions of wallets (e.g. MetaMask, Phantom), exchanges (e.g. Binance), or dApps

Often promoted via Google ads or shared via Discord/X groups, designed to look like a real website

Users may be prompted to “Import wallet” or “Restore funds”, thereby stealing their mnemonics or private keys

Phishing emails and messages

Fake official communications (e.g., “urgent security update” or “account compromised”)

Contains links to fake login portals or directs you to interact with malicious tokens or smart contracts

Some scams even allow you to transfer funds, but they are stolen within minutes.

Airdrop scams, sending fake token airdrops to wallets (especially on EVM chains)

Clicking on a token or attempting to trade a token triggers a malicious contract interaction

Secretly requesting unlimited token approvals, or stealing user native tokens via signed payloads

Phishing Case

In June 2023, the North Korean Lazarus Group hacked Atomic Wallet in one of the most destructive pure phishing attacks in cryptocurrency history. The attack compromised over 5,500 non-custodial wallets, resulting in the theft of over $100 million in cryptocurrency without requiring users to sign any malicious transactions or interact with smart contracts. The attack was conducted solely through a deceptive interface and malware to extract mnemonics and private keys—a classic example of phishing-based credential theft.

Atomic Wallet is a multi-chain non-custodial wallet that supports more than 500 cryptocurrencies. In this incident, the attackers launched a coordinated phishing campaign that exploited users trust in the wallets support infrastructure, update process, and brand image. Victims were lured by emails, fake websites, and Trojan software updates, all of which were designed to mimic legitimate communications from Atomic Wallet.

Phishing methods used by hackers include:

Fake emails pretending to be from Atomic Wallet customer support or security alerts, urging users to take urgent action

Fraudulent websites that mimic wallet recovery or airdrop claiming interfaces (e.g., `atomic-wallet[.]co`)

Malicious updates distributed via Discord, email, and compromised forums that either directed users to phishing pages or extracted login credentials via local malware

Once the user enters their 12 or 24-word mnemonic phrase into these fraudulent interfaces, the attacker gains full access to their wallet. This exploit does not require any on-chain interaction from the victim: no wallet connection, no signature request, and no smart contract participation. Instead, it relies entirely on social engineering and the users willingness to recover or verify their wallet on a seemingly trustworthy platform.

Wallet stealers and malicious authorization

A wallet stealer is a malicious smart contract or dApp that aims to extract assets from a users wallet, not by stealing private keys, but by tricking the user into granting access to tokens or signing dangerous transactions. Unlike phishing attacks (which steal user credentials), wallet stealers exploit permissions - which are at the heart of Web3 trust.

As DeFi and Web3 applications become mainstream, wallets like MetaMask and Phantom have popularized the concept of connecting dApps. This brings convenience, but also huge attack vulnerabilities. In 2021-2023, NFT minting, fake airdrops, and some dApps began to embed malicious contracts into familiar user interfaces. Users often connect their wallets and click Approve out of excitement or distraction, without knowing what they have authorized.

Attack Mechanism

Malicious grants exploit the permission systems in blockchain standards such as ERC-20 and ERC-721/ERC-1155. They trick users into granting attackers continued access to their assets.

For example, the approve(addressspender, uint 256 amount) function in ERC-20 tokens allows a “spender” (e.g., a DApp or an attacker) to transfer a specified amount of tokens from a user’s wallet. The setApprovalForAll(addressoperator, bool approved) function in NFTs grants the “operator” permission to transfer all NFTs in a collection.

These approvals are standard for DApps (e.g., Uniswap requires approval to swap tokens), but attackers can exploit them for malicious purposes.

How an attacker can gain authorization

Deceptive prompts: Phishing sites or infected DApps prompt users to sign a transaction labeled Wallet Connect, Token Exchange, or NFT Claim. This transaction actually calls the approve or setApprovalForAll method of the attackers address.

Unlimited approvals: An attacker would typically request unlimited token authorizations (e.g., uint 256.max) or setApprovalForAll(true) to gain full control over a user’s tokens or NFTs.

Blind Signatures: Some DApps let users sign opaque data, which makes malicious behavior difficult to detect. Even for hardware wallets like Ledger, the details displayed may seem harmless (such as Approve Token), but hide the attackers intentions.

Once an attacker obtains authorization, they may immediately use the authorization information to transfer tokens/NFTs to their wallet, or they may wait (sometimes for weeks or months) before stealing assets to reduce suspicion.

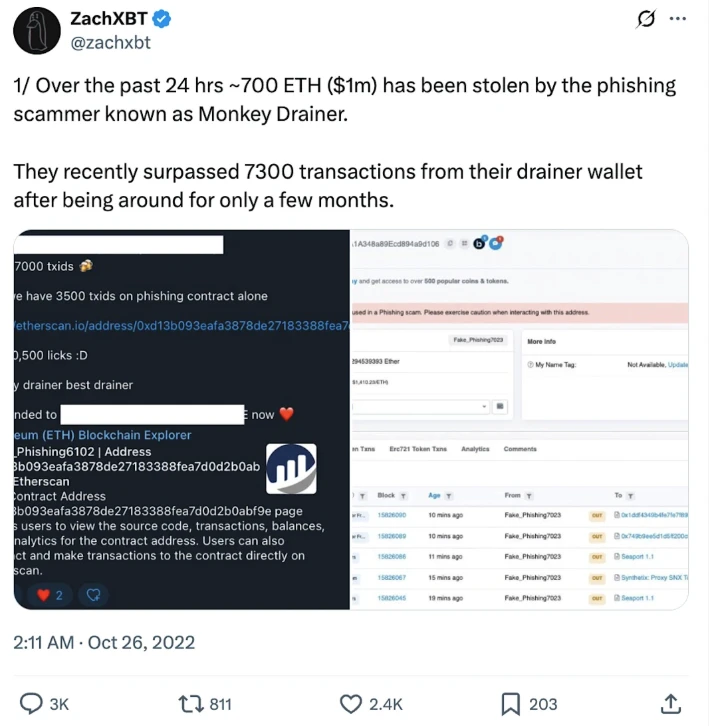

Wallet drainer/malicious authorization example

The Monkey Drainer scam, which occurred primarily in 2022 and early 2023, is a notorious drainer-as-a-service phishing toolkit responsible for stealing millions in cryptocurrency (including NFTs) through deceptive websites and malicious smart contracts. Unlike traditional phishing, which relies on collecting users mnemonics or passwords, Monkey Drainer operates through malicious transaction signing and smart contract abuse, allowing attackers to extract tokens and NFTs without directly stealing credentials. By tricking users into signing dangerous on-chain approvals, Monkey Drainer stole more than $4.3 million in funds from hundreds of wallets before shutting down in early 2023.

Well-known on-chain detective ZachXBT reveals Monkey Drainer scam

The toolkit is popular among low-skilled attackers and is heavily promoted in underground Telegram and darknet communities. It allows affiliated parties to clone fake minting websites, impersonate real projects, and configure the backend to forward signed transactions to centralized withdrawal contracts. These contracts are designed to exploit token permissions, sign messages without the users knowledge, and grant the attackers address access to assets through functions such as setApprovalForAll() (NFT) or permit() (ERC-20 tokens).

Notably, the interaction avoids direct phishing, and victims are not asked for private keys or mnemonics. Instead, they interact with a legitimate-looking dApp, often on a minting page with a countdown or popular branding. Once connected, users are prompted to sign a transaction they don’t fully understand, often obscured by generic authorization language or wallet UI confusion. Rather than transferring funds directly, these signatures authorize the attacker to make transfers at any time. Once authorized, the drainer contract can perform batch withdrawals within a single block.

A major feature of the Monkey Drainer method is its delayed execution, with stolen assets usually being withdrawn hours or days later to avoid suspicion and maximize returns. This makes it particularly effective for users with large wallets or active trading activities, as their authorizations are mixed into normal usage patterns. Some well-known victims include NFT collectors from projects such as CloneX, Bored Apes, and Azuki.

Although Monkey Drainer ceased operations in 2023, presumably to “lay a low profile,” the Wallet Drainer Era continues to grow, posing a continuing threat to users who misunderstand or underestimate the power of blind on-chain authorization.

Malware and device vulnerabilities

Finally, “Malware and Device Exploits” refers to a broader and more diverse set of attacks across a variety of delivery vectors that aim to compromise a user’s computer, phone, or browser to deceptively install malware. The goal is often to steal sensitive information (e.g., seed phrases, private keys), intercept wallet interactions, or allow the attacker to remotely control the victim’s device. In the cryptocurrency space, these attacks often begin with social engineering, such as fake job offers, fake app updates, or files sent via Discord, but can quickly escalate into full-blown system compromises.

Malware has been around since the dawn of personal computers. Traditionally, it has been used to steal credit card information, collect login credentials, or hijack systems to send spam or ransomware. With the rise of cryptocurrencies, attackers have shifted from targeting online banking to stealing crypto assets, where transactions are irreversible.

Most malware does not spread randomly, it needs the victim to be tricked into executing it. This is where social engineering comes into play. Common ways of spreading are listed in the first section of this article.

Malware and device vulnerability example: Axie Infinity recruitment scam in 2022

The 2022 Axie Infinity recruitment scam led to the massive Ronin Bridge hack, a classic example of malware and device exploits in the cryptocurrency space, with sophisticated social engineering behind them. The attack, attributed to the North Korean hacking group Lazarus Group, resulted in the theft of approximately $620 million in cryptocurrency, making it one of the largest decentralized finance (DeFi) hacks to date.

Axie Infinity vulnerability reported by traditional financial media

The hack was a multi-stage operation that combined social engineering, malware deployment, and blockchain infrastructure vulnerability exploitation.

Posing as a recruiter for a fictitious company, the hackers used LinkedIn to target employees of Sky Mavis, the company that operates Ronin Network, an Ethereum-linked sidechain that powers the popular “play and earn” blockchain game Axie Infinity. At the time, Ronin and Axis Infinity had market caps of approximately $300 million and $4 billion, respectively.

The attackers approached multiple employees, but their primary target was a senior engineer. To build trust, the attackers conducted multiple rounds of fake job interviews and lured the engineer with extremely generous salary packages. The attackers sent the engineer a PDF document disguised as a formal job offer. The engineer mistakenly believed it was part of the recruitment process and downloaded and opened the file on a company computer. The PDF document contained a RAT (Remote Access Trojan) that, when opened, compromised the engineers system, allowing the hackers to access Sky Mavis internal systems. This intrusion provided the conditions for attacking the infrastructure of the Ronin network.

The hack resulted in the theft of $620 million worth of ETH (173,600 ETH and $25.5 million USDC), of which only $30 million was ultimately recovered.

How should we protect ourselves

While exploits are becoming more sophisticated, they still rely on some telltale signs. Common red flags include:

“Import your wallet to claim X”: No legitimate service will ask you for your seed phrase.

Unsolicited private messages: especially those claiming to offer support, funding, or help with a problem you didnt ask about.

The domain name is slightly misspelled: for example, metamusk.io vs. metarnask.io.

Google Ads: Phishing links often appear above genuine links in search results.

Offers that seem too good to be true: For example, “Get 5 ETH” or “Double Token Bonus” offers.

Emergency or scare tactics: “Your account has been locked”, “Claim now or lose your funds”.

Unlimited Token Approval: Users should set the number of tokens by themselves.

Blind Signature Request: Hexadecimal payload, lacking human-readable interpretation.

Unverified or obscure contracts: If the token or dApp is new, check what you are approving.

Urgent UI prompt: A typical pressure tactic, such as You must sign now or you will miss the opportunity.

MetaMask weird signature pop-up: Especially in cases where the requirements are unclear, gas-free transactions, or contain function calls you dont understand.

Personal protection law

To protect ourselves, we can follow these golden rules:

Never share your recovery phrase with anyone for any reason.

Collect the official website: Always navigate directly and never use search engines to search for wallets or exchanges.

Don’t click on random airdrop tokens: especially for projects you haven’t participated in.

Avoid unauthorized private messages: Legitimate projects rarely private message first… (unless they actually do).

Use hardware wallets: They reduce the risk of blind signatures and prevent key compromise.

Enable phishing protection tools: Use extensions like PhishFort, Revoke.cash, and ad blockers.

Use a read-only browser: Tools like Etherscan Token Approvals or Revoke.cash can show you what permissions your wallet has.

Use a one-time wallet: Create a new wallet with zero or small amounts of funds to test minting or linking first. This will minimize losses.

Diversify your assets: Don’t keep all your assets in one wallet.

If you are already an experienced cryptocurrency user, here are some more advanced rules to follow:

Use a dedicated device or browser profile for cryptocurrency activities. Also, use a dedicated device to open links and direct messages.

Looking at Etherscan’s coin warning tab, many scam coins have been flagged.

Cross-verify the contract address with the official project announcement.

Double-check URLs: Especially in email and chat, subtle typos are common. Many instant messaging apps, and of course websites, allow for hyperlinks — which makes it possible for someone to click directly on a link like www.google.com.

Pay attention to signatures: Always decode transactions (e.g., via MetaMask, Rabby, or a simulator) before confirming them.

Conclusion

Most users believe that vulnerabilities in cryptocurrencies are technical and inevitable, especially those new to the industry. While this may be true for sophisticated attack methods, many times the initial steps are to target individuals in non-technical ways, which makes subsequent attacks preventable.

The vast majority of personal losses in this space come not from some newfangled code bug or obscure protocol vulnerability, but from people signing documents without reading them, importing their wallets into fake apps, or trusting a seemingly legitimate DM. These tools may be new, but their tactics are old: deceiving, urging, misleading.

Self-custody and permissionless features are advantages of cryptocurrencies, but users need to remember that such features also make risks higher. In the traditional financial field, if you are cheated, you can call the bank; in the cryptocurrency field, if you are cheated, the game is probably over.